Over the last week or so, the UK has experienced what can be best described as duration risk in their fixed income markets. It has been equivalent in magnitude, for some, to an extinction-level event. And truthfully speaking, a pension fund going insolvent in the financial markets is equivalent to a meteor wiping out civilisation.

While I’ve seen duration being misquoted as an interchangeable synonym for ‘term to maturity’, in modern fixed income portfolios, ‘duration’ describes far more than a length of time.

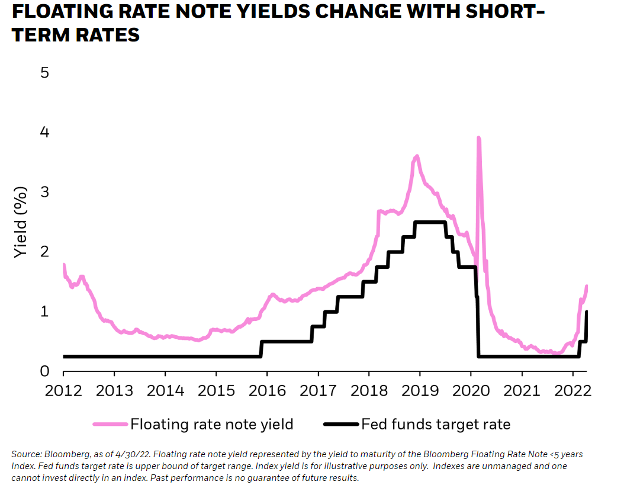

Bond prices move inversely with interest rates. With rates rising in 2022, investor bond portfolios may be underwater. Duration is the responsiveness of the change in bond prices to changes in interest rates – and progressively, this change becomes non-linear. Those seeking to protect their bonds might reduce risk by holding cash or shorter maturity bonds. Others might adjust their strategy and hold their bonds to maturity. In a rapidly rising yield environment driven by global inflationary pressures, private debt offers returns that are more attractive than traditional fixed income securities, which typically carry more duration risk – that is, the risk of capital loss when bond yields are rising, as we’ve been seeing this year.

Private debt returns are typically ‘floating rate’ in nature, with lower (nearer to zero) duration risk. Returns are driven by a spread over a benchmark rate, depending partly on the credit quality of the borrowing party. Borrowers in the private debt market tend to be mostly private entities that find it more expedient to borrow through such channels. This means private lenders can more readily dictate loan terms, benefit from greater control, and capture a higher premium due to a more captive audience. Direct lending is also less volatile relative to public fixed income assets, given that these private credit assets, including lend-out and hold assets, are not publicly traded and are not typically valued on any regular basis. As such, they are not subject to daily market-to-market pricing.

Unlike listed debt, private credit is less transparent— it is not rated by credit rating agencies. Though funds managing private credit are. When paying a floating rate that varies with market conditions, borrowers may find themselves strained when market rates rise, as is the case with many other debt instruments. However, investors benefit when rates are rising.

An added layer of security arises from the bespoke nature of private lending and the hyper specialisation of private credit fund managers. They build relationships with the entities and the projects they finance, negotiate protections, and understand their borrower well. The two sides can work out problems during times of financial stress.

Ultimately as the world readjusts to a post-covid, non-zero interest world, solutions (forcibly or otherwise) have become more bespoke. We believe it is a worthwhile exercise for investors to reconsider private credit, especially in times of heightened uncertainty.