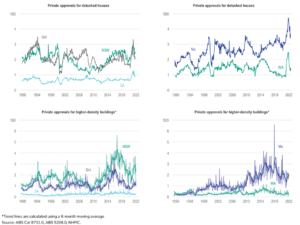

Despite mounting economic uncertainty, the biggest issue for apartment markets nationally is not demand but supply.

First, a sudden unanticipated rise in construction costs has disrupted the entire project pipeline. Invalidating previous project feasibilities, rising costs have resulted in projects being delayed or cancelled, and in some cases, just labelled “pending further review”.

The inevitable collapse of building companies and the subsequent difficulty in replacing them has again caused delays. Projects are being scrapped altogether and developers are having to return pre-sale purchasers’ deposits. Creative solutions involve re-negotiating with buyers to revise prices and switching to a build-to-rent (BTR) model. These things have ensured that the project will be delivered – however the question of “when” remains unanswered.

The net effect of all this is a severe bottleneck in the supply pipeline of apartments.

As evidenced above, approvals and completions have fallen across all dwelling types since 2021, and apartments are no different. Rising interest rates will have spillover effects on the broader housing market through a multitude of macroeconomic channels, including currency, borrowing, and financing effects.

However, the question I ask the most (in wearing both my developer and lender hat) is whether demand going to be resilient in the face of volatile market conditions.

Will there be a flight to affordability? Yes.

Will developers be able to rely on downsizers? Yes.

Will the market benefit from the return of migrants and interstate/international students over the next year? Yes.

In any event, despite the improving demand prospects, the supply of apartments will remain below previous records. And we can rely on supply levels staying low for at least several more years beyond that. So, a persistent imbalance in supply, in an already tight rental market, will only add to the perceived apartment shortage.

The unprecedented nature of the current market has created challenges, yes – but also the opportunity to fix them. Enter the institutional investor. Investing in high-density residential projects can offer institutional investors diversification and stabilised long-term returns, compared to traditional commercial asset classes. Investors will be attracted by the presence of a captive (rental) audience, at least in the near term, and institutionally developed rental apartments will be crucial in providing a critical source of housing supply in Australia.

There is also the opportunity to go further and establish a private-institutional partnership. This would offer institutional investors access to a wide range of residential asset classes, while ensuring that the “little guy” private developers are also able to compete and operate beyond just apartments. Together with an infusion of capital, this kind of expansion will open more of the residential sector to competition, therefore attracting tenants.

A shortage seldom has an easy fix, especially if the problem is in the supply chain. Whatever the remedy, it usually results in either paying too much or waiting around for things to stabilise. But with construction companies themselves falling among rising costs, the bottlenecks aren’t as palatable, and in some way or another, these failings reduce profitability or pass on the expenses to the end consumer. Adding to this the limited avenues of capital available for the residential sector, a new form of partnership between private developers and institutional sources of capital while looking beyond large-scale apartment projects, is both well aligned and equitable for all parties.